One of the oldest and most prevalent conventions in palaeoartistry is the 'monsterising' of extinct species, where deliberate efforts are made to depict prehistoric subjects as more formidable and intimidating than they likely were in life. If you've got even a passing interest in prehistory you'll have seen plenty of examples of such artworks. The prehistoric animals of most films are monsterised to greater or lesser extents, as are those adorning the covers of many popular books on dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates. Even museums and educators regularly employ monsterised depictions of extinct animals.

Monsterisation is achieved in a few ways. It might involve restoring animals as especially lean and vicious, giving them minimised soft-tissues (e.g. 'shrink-wrapping'), conspicuous teeth and claws, or posing them in aggressive dynamism. Compositions that focus on dangerous anatomies, that use proportion-distorting foreshortening to make jaws or talons look particularly imposing, or that have backgrounds recalling dark fantasy settings are also common components of monsterised palaeoart. Monsterisation is not restricted to violent or aggressive depictions either: it can apply to any subject or any scene. Conversely, palaeoartworks featuring blood or violence are not always monstrous, they only become so when these elements are overemphasised or fetishised by their artists.

The decision to restore prehistoric animals as monsters is artistic, not scientific. It is entirely possible, and probably more scientifically credible, to restore ancient animals in naturalistic ways even when they are engaged in potentially violent acts, like predation. Here, Velociraptor mongoliensis chases down Zalambdalestes lechei. The choice to show this famous movie villain pursuing small prey is at odds with our cinematic experiences, but is also far more consistent with the behaviour of living predators.

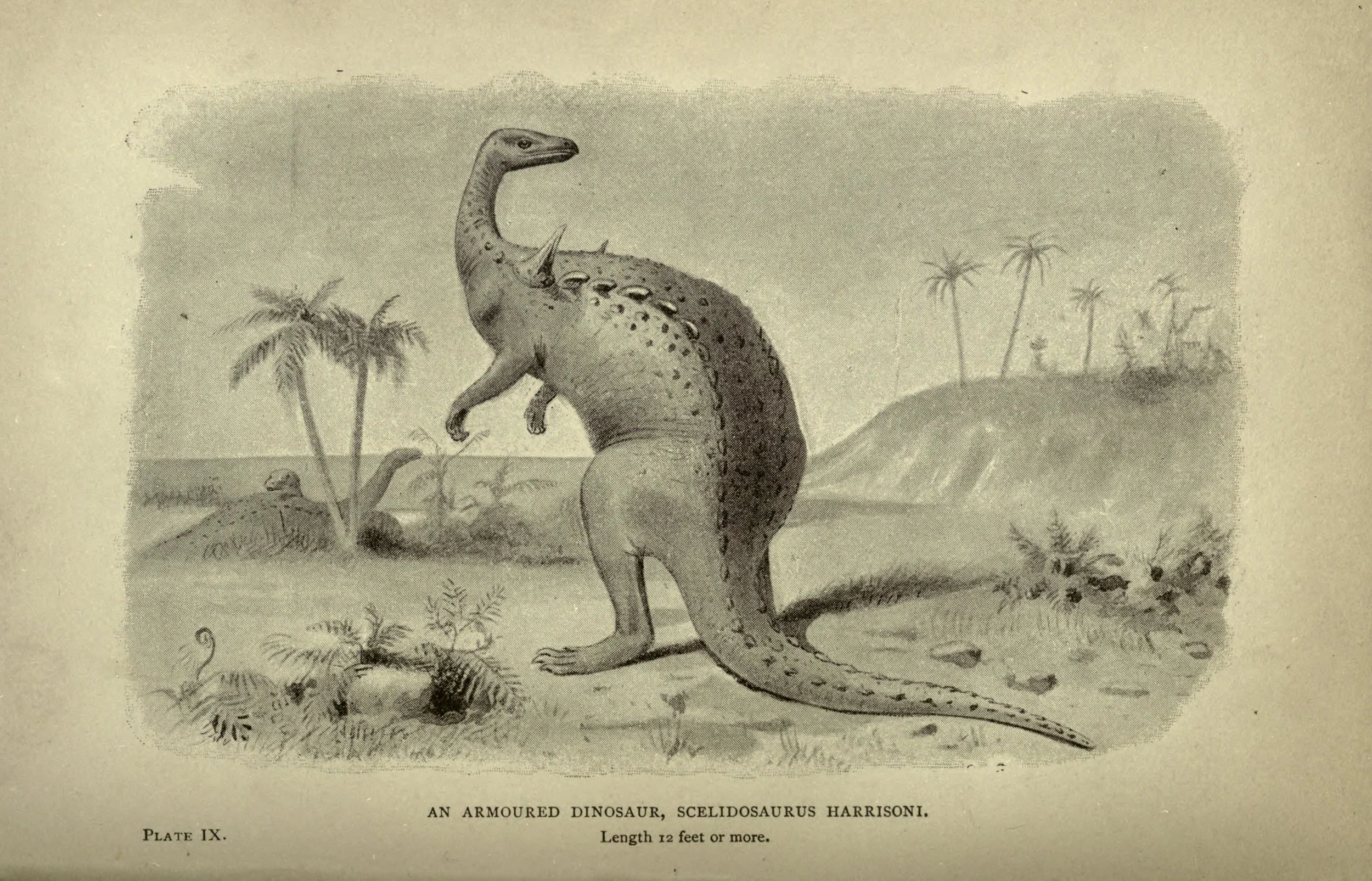

Monsterisation is almost as old as palaeoart itself. The oldest known scientifically informed palaeoartworks date to 1800 (Taquet and Padian 2004) and within just a few decades prehistory was being restored with a monstrous edge. Early examples include the draconian pterosaur featured in Reverend Howman's 1829 Noctivagus Dragon, de la Beche's extremely violent Duria Antiquior (1830), and the grim primordial scenes of John Martin, such as The Country of the Iguanodon (1837). Not all early illustrators and scientists were portraying extinct animals this way, however. Georges Cuvier approached his reconstructions with a predictable level of anatomical objectiveness, and much of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins' work, including his famous Crystal Palace restorations, was naturalistic and grounded. This dichotomy in approaches reflects the fact that there are no anatomical correlates for monstrousness. Whether an ancient animal is monsterised or not is entirely an artistic choice, the deliberate emphasising of brutishness over a more holistic and objective reading of palaeontological and zoological data. The unspoken idea that certain features should lead to greater monsterisation is refuted by the great number of extant species with stereotyped ‘monstrous’ features - giant size, large teeth, horns, or claws - which are far from terrifying in appearance or behaviour.

It's tempting to link the artistic monsterisation of prehistory to changes in Western culture during the last 200 years, especially to shifting attitudes to religion and evolution, as well as the establishment of prehistoric animals as marketable pop culture. 19th century science sought to align Christian doctrine with then new data concerning geology and extinct animals, and also regarded Western civilisation as the acme of Creation. Accordingly, artists such as John Martin and Édouard Riou, who were no strangers to rendering biblical scenes, reconstructed ancient animals as denizens of a violent, Godless world unfit for human habitation. Later artists such as Knight, Zallinger and Burian, were not working under this strict religious framework but the idea that man and the modern age were somehow special lingered in the form of orthogenic evolutionary concepts. While not the most overt monsteriser, some of Charles Knight's extinct reptile restorations have a tinge of exaggerated savagery, and comments in his books (e.g. Knight 1935, 1946) leave little doubt that he regarded Mesozoic reptiles as monstrous, brutish things. Conversely, he regarded extinct mammals as noble, intelligent and behaviorally complex. Humanity, one of Knight’s favourite subjects, continued to hold a special place in the order of things.

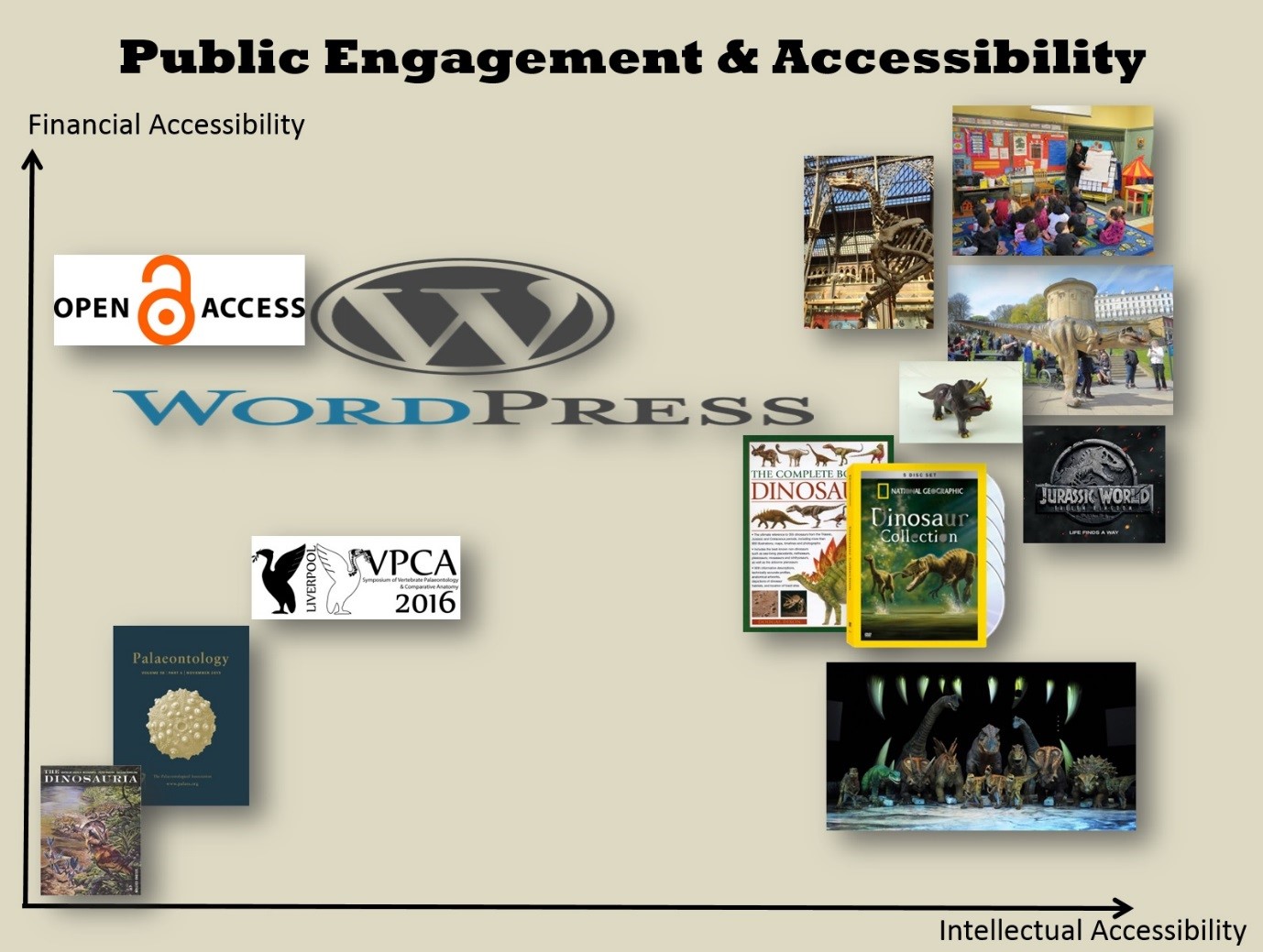

Today, perhaps the most significant driver of palaeoartistic monsterisation is a commercial one. Violent, savage prehistory has been a proven money-maker since at least the early 20th century and it's now popular books, comics, and blockbuster films that harbour the most monsterised prehistoric species. An evolution of the convention has seen modern media involving us, their audience, in the monsterisation process. We are now the targets of aggressively restored animals which lunge from their products towards us, mouths agape and claws bared. This relatively recent trend surely draws inspiration from the highly foreshortened palaeoart popularised by Luis Rey, and there are now hundreds of products using this theme. Viewer-targeting monsterised theropods are surely the most significant stereotype of modern palaeoart.

The results of Google image search for ‘dinosaur book’ or ‘dinosaur DVD’: dozens and dozens of prehistoric animals (mostly theropods) that want to eat our faces.

Monsterisation thus dominates the majority of popular palaeontological media and palaeoart, to the extent that some conventions - open-mouth roaring, fights and violence, the fetishising of claws and teeth - are so entrenched that clients regard them as essential in all new palaeoart. I’ve certainly experienced this myself when creating PR images for scientists, leading to sometimes difficult conversations about compositional storytelling, the scientific basis for visible teeth and claws, and exactly how animals behave in predatory scenarios. Perhaps this reflects fears that new products or artwork will be overlooked if they do not follow wider marketing trends for prehistoric outreach and merchandise? Notably, even products of primarily academic or educational remit, or those aimed at older audiences, often feature screaming, roaring dinosaurs, making them indistinguishable from those targeted at young children.

But does it really matter if artistic takes on prehistory are monsterised? As someone keen to promote a science-led and naturalistic view of ancient animals, it’s easy to take a purist perspective where monsterisation is framed as a corruption of palaeontological data - a portrayal of a violent prehistory that likely never existed. But could we look more favourably on it, perhaps admitting that such artwork is merely being infused with excitement and optimised for promotion? Could it even be a useful convention, helping palaeoart and associated products appeal to audiences beyond natural history enthusiasts?

I suspect the value of monsterisation falls between these two extremes. The proven marketing success of vicious, snarling prehistoric species means that palaeontological subjects are pasted on the side of buses and billboards while other sciences struggle for public attention. While it’s frustrating to see incredulous takes on prehistory being featured so widely, perhaps we should be grateful that it helps palaeontology maintain such a prominent public face, and for the outreach springboards it provides. The public at large may have a very distorted view of what Velociraptor was and looked like, but at least they’ve heard of it. On the other hand, many pieces of monsterised artwork distort well-established facts of life appearance or likely behaviour of their subjects, leaving educators with the task of deconstructing misinformation during outreach events instead of imparting new ideas. This creates a sense that we are progressing little in conveying what prehistory was like because basic aspects of anatomy or behaviour have to be continually clarified.

More positively, monsterised palaeoart clearly has a following and can be profitable. It does not appeal to everyone, but there’s nothing wrong with enjoying monsterised prehistory, and even paying for it, if that’s what people desire. I admit to having concerns about the absence of a mainstream alternative however, as the ubiquity of monsterised palaeoart makes the genre look stereotyped, unimaginative and unsophisticated compared to other branches of natural history art. This is worsened by the fact that a lot of monsterised palaeoart is technically and scientifically poor as well as crudely composed, giving it an air of pulpy cartooniness. The visibility of so much poorly-executed art of animals with big teeth, big claws and big roars does nothing to dissuade the public that palaeontology is anything more than low-grade 'kids stuff', and undermines palaeoart as a mature and skilled artform with depth, history and nuance.

A concern without silver lining is how monsterised palaeoart separates prehistoric life from species alive today. Monsterisation brings fantastic and supernatural elements to prehistoric species which gives them an otherworldly quality. They do not look like they belong to the same tree of life as modern species, and their dark, low-key environments resemble film sets rather than actual habitats. This is a problem. Dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals are lauded as a gateway to science, a means to educate on important topics such as scientific methods, ecology, extinction and even climate change by stealth. But we undermine this by presenting prehistory as a fantasy world populated by fighting gargoyles. Any discussion we have of palaeoecology, evolution or biological vulnerability featuring monsterised artwork overshadows our points with visual fictions, informing audiences that these animals were somehow more fantastical than extant species, and therefore of lessened relevance to understanding modern times. Restoring extinct animals in more relatable, grounded ways makes our educational messages far more on point. We can communicate ideas about fossil species as real animals far more effectively if we show them as real animals as well.

And this brings me to my ultimate question: whether monsterised palaeoart qualifies as ‘real’ palaeoart at all, and if those of us involved in palaeontological outreach and education should be making a conscious effort to move away from it. Palaeoart is defined as being evidence-driven and its success depends in part on an ability to reflect all available data on a subject’s predicted life appearance and behaviour. Monsterisation cherry picks this data however, selecting anatomies and behaviours that suit edgy portrayals but overlooking data hinting at less ferocious or more grounded restorations. Art of a monsterised prehistory is therefore certainly inspired by palaeontology, but I cannot regard it as palaeoart in a true sense. This might seem like pretentious artistic noodling or even snobbery - does it matter if monsterised depictions are ‘real’ palaeoart or not? - but if we concede that such artworks are not reflective of scientific data about ancient animals, then what value does that art have to educators and scientists?

We must remember that the visuals chosen by educators and science communicators are seen as an endorsement of their content by a trusting public, and that artwork is often more informative and memorable than written or spoken content. There are plenty of alternatives to monsterised palaeoart if bold and interesting palaeoartworks are needed (see, for example, the naturalistic but stylised work of Ray Troll, Rebecca Groom, Raven Amos, David Orr or Johan Egerkrans), nor we should not underestimate the power of traditional palaeoartistic approaches to inspire and invigorate. Where education is concerned, we might do better to explore visually arresting but scientifically credible takes on prehistoric species, but to leave the monsters in the fantasy realms where they belong.

References

● Taquet, P., & Padian, K. (2004). The earliest known restoration of a pterosaur and the philosophical origins of Cuvier’s Ossemens Fossiles. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 3(2), 157-175.

● Knight, C. R. (1935). Before the dawn of history. Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Incorporated.

● Knight, C. R. (1946). Life through the ages. Alfred A.Knopf, Inc.